Multiplayer Architecture - Part 2: Player movement

In the previous article, we discussed basic client-server models and basic networking concepts. In this article, we are going to talk about basic synchronisation of world simulation, and player movement.

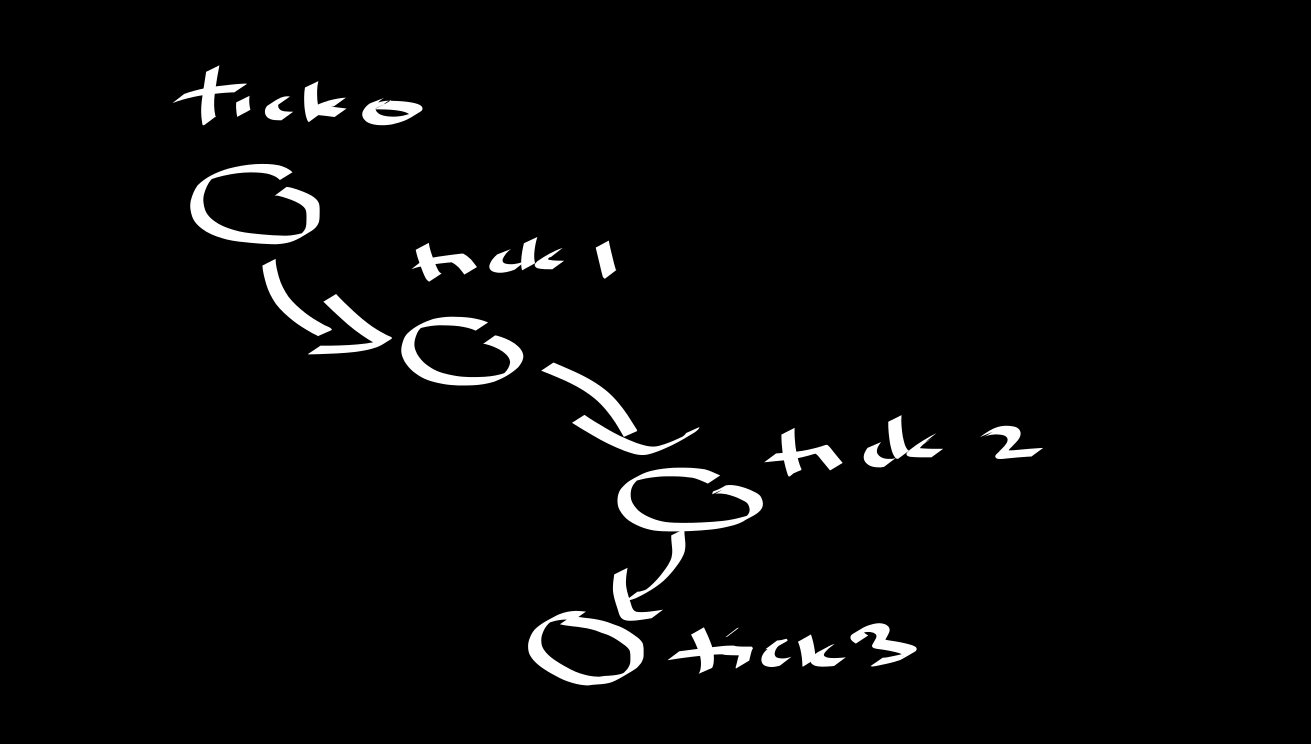

Tick

A tick is basically a simulation step. You can imagine it with the following pseudo-code:

float delta_time;

void game_loop() {

while (true) {

float tick_start = current_time();

do_simulation(delta_time);

render();

float tick_end = current_time();

float delta_time = tick_end - tick_start;

}

}Often times, you want the delta time, or the timestep, to be fixed, for example at 60 Hz. In which case you would do something like this:

float delta_time;

void game_loop() {

while (true) {

float tick_start = current_time();

do_simulation(delta_time);

render();

float tick_end = current_time();

float delta_time = tick_end - tick_start;

// Waits until delta_time becomes 1 / 60 seconds

wait_until_tick_end(delta_time);

}

}The concept of the tick is quite important as it will serve as a base for the following information.

Client and Server delay

One thing that you will get used to is the fact that there is quite a lot of latency between clients and servers (up to a couple hundred milliseconds). This means that everytime the client sends something to the server, there is a delay, but for that client to receive information back, there is again that same delay.

The server will be receiving information from all the clients. With this information, the server will have the responsibility of making sure that clients stay in sync, by dispatching the game state to all clients at certain intervals (in this game, 25 ms).

Sending input to the server

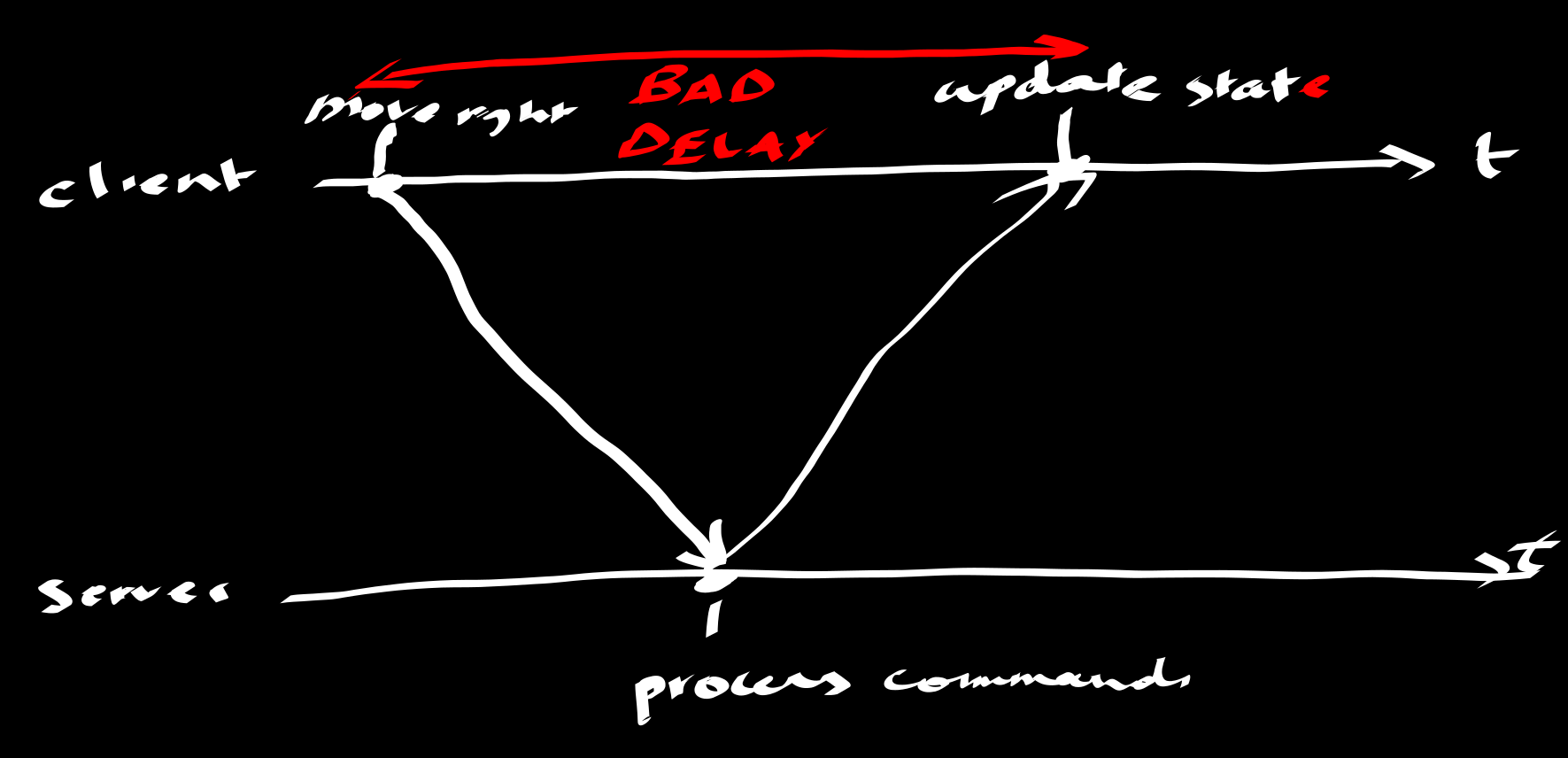

To avoid cheating, as we established in the previous article, we will make the server autoratative. This means that we cannot trust the clients to calculate their positions / directions from key strokes and mouse. The client will have to wait for the server to send the game state back to update their information. But, there is a problem with that:

As you can see, if we always for the server to repsond with game state to update the local information, we could constantly be subject to huge delays. To fix this, we must implement client-side prediction.

Client-side prediction

In this scenario, we still send all our commands to the server for it to process it, but at the same time, the client will run the simulation for the player that it controls, so that when, for example, you press a key, you instantly move. This is great for fast paced games as it gives the illusion that there is no latency. The client therefore basically predicts where the server will say it will be.

Prediction errors

It is unfortunately possible that prediction errors may occur: floating point inprecision, UDP packet loss… In order to take into account this issue, we must implement prediction error handling. Now, the clients always not only send the key strokes / mouse input, but also send their predicted positions / view directions / etc. When the server receives this, it will process the commands, and then check if the clients’ predicted data is wrong. If it is wrong, it will tell the client to correct its state.

Player interpolation

Now that we have established how to handle sending input / prediction error correction, we must now take into account the other 20 or so players that we will be playing with. Every 25 ms, when the server dispatches the game state to the clients, it will also send the current position / view direction of all the other players.

When a client receives this game state packet, it will simply push this “snapshot” into an array of player state snapshots for each player, and linearly interpolate between each snapshot over multiple frames.

And voila! That is basic player movement handling in multiplayer!

There are of course a couple problems (the fact that clients will only ever see other clients back in time…), which we will address when more time critical things get implemented (like shooting, and so on…). But believe or not, this is pretty much how it usually works!

The only problem is that we still haven’t implemented physics, player movement is literally just simple WASD, SPACE, LEFT SHIFT, for going forward, left, back, right, up and down - you are just flying around. We still haven’t gone into how chunks will be handled over the network, that will be the next step.

Of course, despite the fact that on paper, this doesn’t sound too bad to code, actually implementing it will prove otherwise… In the next article, I will go over how I actually implemented basic player movement synchronisation in the engine.